Poetry

April 1-26, 2019

Open to All

Tiered Tuition

$0-$0 Reserve My Spot This offering is not currently available for registration. Please check back or email Jennifer Jean at jjean@fawc.org for any questions.

In this workshop, we’ll look at how each poem takes an organic form, and how discovery of that form can lead us more fully into the poem.

At one point I had a sequence of mostly short poems that refused to come together as a whole. One afternoon, while, not wearing my glasses and so unable to read and get caught up in the words, I realized looking at them as shapes that they were incipient sonnets. This realization made me feel something like—oh no! I don’t want to write sonnets! But the poems seemed to insist upon that form, and so I followed their prompting. As I rewrote them as sonnets, I further realized that they were a crown of sonnets (the last line of each becoming the first line of the next) but that, in this case, they had to be a broken crown, only part of the line carried over, echoing the poem’s imagery in the middle of the sequence.

My sense of form in poetry is that just as different species of creatures take on a specific morphology so do poems. Even those written as free verse may need specific stanzas, spacing on the page, and length of line.

We’ll begin by looking at a few traditional formal examples—how the sonnet lends itself to conflict in thought, how the villanelle is given to obsession, and how even the simple couplet creates a two-step that can cleave together and cleft apart. We’ll then approach our own work, writing new poems or working with those that have not yet fully arrived on the page, while using form as a key to open the door to new possibilities.

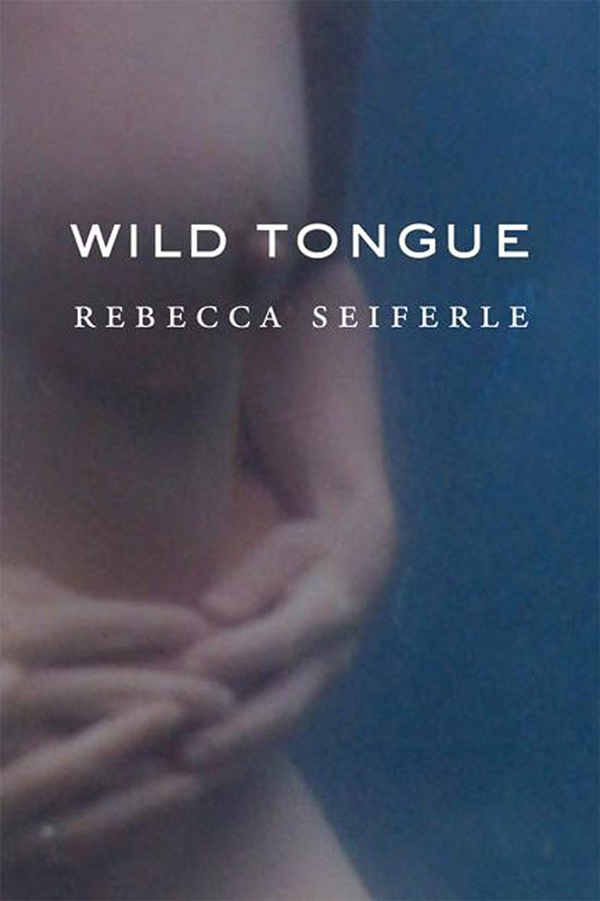

Rebecca Seiferle’s poems are forthcoming in Essential Queer Voices of U.S. Poetry in early 2024 from Green Linden Press. She has published four poetry collections. Wild Tongue (Copper Canyon) won the Grub Street National Book Prize in Poetry. Her three previous collections, Bitters, The Music We Dance To and The Ripped-Out Seam won the Western States Book Award, a Pushcart Prize, The National Writer’s Union Prize, and the Poets & Writers Exchange Award. Seiferle is also a noted translator, having translated César Vallejo’s The Black Heralds (Copper Canyon) and Trilce (Sheep Meadow Press). She was Jacob Ziskind poet-in-residence at Brandeis University, and a visiting writer at Vanderbilt University, Hamilton College, the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the Key West Literary Seminars, the Summer Literary Seminars in Lithuania, StAnza International Poetry Festival in St. Andrews, Scotland, among others. She was the recipient of the Lannan Literary Fellowship for Poetry. From 2012-2016 Seiferle was Tucson Poet Laureate and she was awarded an Arizona Commission on the Arts Research and Development Grant in 2019.